US President Biden gave a speech today defending his decision to pull US combat forces out of Afghanistan. The decision is in a very real sense not surprising: Presidents Obama and Trump also wanted to end US combat operations in Afghanistan, but neither had the will to pay the political price for the decision. Both feared the charge that has haunted US foreign policy throughout the Cold War and post-Cold War periods: “Who lost China? Who lost Cuba? Who lost Vietnam? The fear of losing a war has been one of the most insidious drivers of American foreign policy since 1945, a fear rooted in a misbegotten legacy of Neville Chamberlain’s “loss” of Czechoslovakia as one of the catalysts for the Second World War.

Prime Minister Chamberlain and Chancellor Hitler at Munich in 1938

This fear also motivated US decision makers to prop up dictators in Guatemala, Nicaragua, the Congo (now Zaire), Iran, Grenada, and numerous other countries lest they be accused by their political opponents of being soft on the “enemy” whether the enemy be Communist, terrorist, or Islamist. And these decision-makers made decisions that they knew were self-defeating. President Lyndon Johnson, for example, continued the war in Vietnam even though he believed that it was not in the national interest. Here is an excerpt from a transcript of a telephone discussion between President Johnson and his National Security Adviser, McGeorge Bundy, in 1964:

Johnson: I will tell you the more, I just stayed awake last night thinking of this thing, and the more that I think of it I don’t know what in the hell, it looks like to me that we’re getting into another Korea. It just worries the hell out of me. I don’t see what we can ever hope to get out of there with once we’re committed. I believe the Chinese Communists are coming into it. I don’t think that we can fight them 10,000 miles away from home and ever get anywhere in that area. I don’t think it’s worth fighting for and I don’t think we can get out. And it’s just the biggest damn mess that I ever saw.

Bundy: It is an awful mess.

Johnson: And we just got to think about it. I’m looking at this Sergeant of mine this morning and he’s got 6 little old kids over there, and he’s getting out my things, and bringing me in my night reading, and all that kind of stuff, and I just thought about ordering all those kids in there. And what in the hell am I ordering them out there for? What in the hell is Vietnam worth to me? What is Laos worth to me? What is it worth to this country? We’ve got a treaty but hell, everybody else has got a treaty out there, and they’re not doing a thing about it.

Bundy: Yeah, yeah.

Decision-makers were also motivated by the illusion that non-Americans would naturally wish to live within political and economic institutions that were similar to those in the US–that representative democracy and market capitalism were inherently desirable. The attitude is generally described a a belief in American exceptionalism and Professor Stephen Walt does a nice job of eviscerating the myth. But Stanley Kubrick savages the myth in the film Full Metal Jacket.

One can easily detect in the speech President Biden’s fear of being tagged as the President who “lost” Afghanistan and I am certain that some will make that accusation if Biden runs again for President in 2024:

“The status quo was not an option. Staying would have meant U.S. troops taking casualties; American men and women back in the middle of a civil war. And we would have run the risk of having to send more troops back into Afghanistan to defend our remaining troops.

Once that agreement with the Taliban had been made, staying with a bare minimum force was no longer possible.

So let me ask those who wanted us to stay: How many more — how many thousands more of America’s daughters and sons are you willing to risk? How long would you have them stay?”

President Biden made a crucial distinction between what happened in October 2001 in Afghanistan and what is happening now, a distinction that separates realism from idealism:

“As I said in April, the United States did what we went to do in Afghanistan: to get the terrorists who attacked us on 9/11 and to deliver justice to Osama Bin Laden, and to degrade the terrorist threat to keep Afghanistan from becoming a base from which attacks could be continued against the United States. We achieved those objectives. That’s why we went.

“We did not go to Afghanistan to nation-build. And it’s the right and the responsibility of the Afghan people alone to decide their future and how they want to run their country.

That distinction is critical if one is to engage in a discussion about what winning and losing in Afghanistan actually meant. When the US invaded the country in 2001, the only objective stated by then President George W. Bush was the realist objective of eliminating an imminent threat to the US national interest:

“And tonight the United States of America makes the following demands on the Taliban.

“Deliver to United States authorities all of the leaders of Al Quaeda who hide in your land.

“Release all foreign nationals, including American citizens you have unjustly imprisoned. Protect foreign journalists, diplomats and aid workers in your country. Close immediately and permanently every terrorist training camp in Afghanistan. And hand over every terrorist and every person and their support structure to appropriate authorities.

“Give the United States full access to terrorist training camps, so we can make sure they are no longer operating.

“These demands are not open to negotiation or discussion.

“The Taliban must act and act immediately.

“They will hand over the terrorists or they will share in their fate.”

Unfortunately, these objectives morphed into a far more ambiguous and ill-informed set of objectives that reflected virtually no understanding of the history or culture of the peoples who inhabit the territory that was shaped by the imperial desires of Britain and Russia in the nineteenth century into an ersatz nation-state called Afghanistan in 1921. After 100 years, Afghanistan still defies the Western template of a nation-state and whatever happens after the US pull-out will reflect, one hopes, the disparate interests of the people who live within that territory.

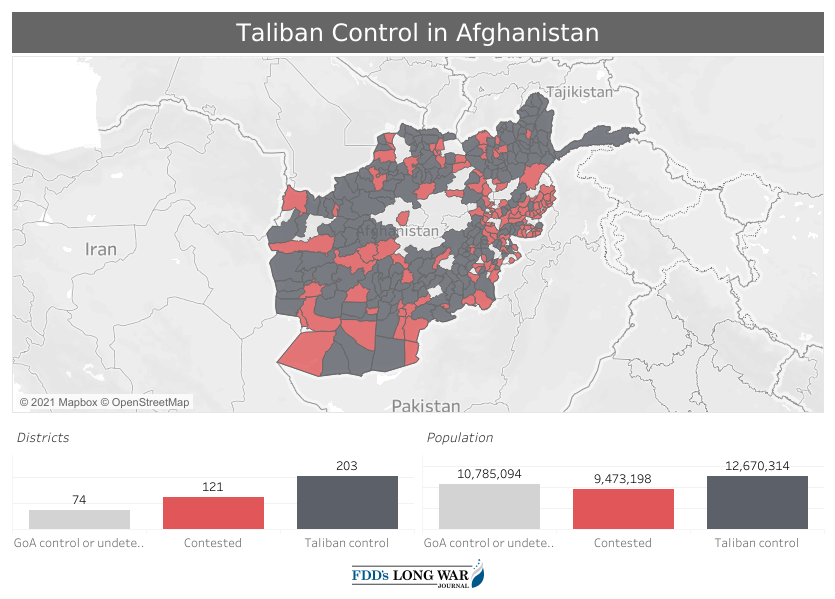

The Taliban already control large swathes of territory and it may eventually topple the Afghan central government. But that eventuality would occur in the context of a civil war whereas the war is now an international war. I am not sure that the difference between and international and a civil war is particularly meaningful to the innocents who are always the victims of war. And then the Taliban would have to figure out how to govern and it is not clear that it has the capability to govern any more effectively than the current central government, particularly since there are not many states that would subsidize the Taliban more than the US was willing to subsidize the current government. So I would expect the violence to continue whether the US stayed or left.

There are two groups, however, which will suffer disproportionately. First, those who supported the US and allied operations, such as translators and local contractors, will likely be targeted by the Taliban as traitors. It appears as if President Biden is aware of the US responsibility to protect these people:

“We’re also going to continue to make sure that we take on the Afghan nationals who work side-by-side with U.S. forces, including interpreters and translators — since we’re no longer going to have military there after this; we’re not going to need them and they have no jobs — who are also going to be vital to our efforts so they — and they’ve been very vital — and so their families are not exposed to danger as well.

“We’ve already dramatically accelerated the procedure time for Special Immigrant Visas to bring them to the United States.

“Since I was inaugurated on January 20th, we’ve already approved 2,500 Special Immigrant Visas to come to the United States. Up to now, fewer than half have exercised their right to do that. Half have gotten on aircraft and com — commercial flights and come, and the other half believe they want to stay — at least thus far.

“We’re working closely with Congress to change the authorization legislation so that we can streamline the process of approving those visas. And those who have stood up for the operation to physically relocate thousands of Afghans and their families before the U.S. military mission concludes so that, if they choose, they can wait safely outside of Afghanistan while their U.S. visas are being processed.”

It is incredibly important that the American people hold President Biden to keep that solemn promise.

The second group who will suffer disproportionately from the American withdrawal are the Afghan women who took advantage of the opportunity to educate themselves and to prepare themselves for positions in the workplace. The earlier Taliban regimes brutally repressed these aspirations and it is likely that there remain strong elements within the Taliban who wish to continue such policies. But there are some women in Afghanistan who believe that at least among the urban elite, some of these gains may persist. I remain pessimistic on this score and hope that any future US humanitarian assistance to Afghanistan, which I regard as a moral imperative, will try to protect the interests of women and girls in Afghanistan.

There is no path forward in Afghanistan that does not create some profound elements of tragedy after a US withdrawal. But there is also no path forward in Afghanistan with continued US presence that does not also involve other profound elements of tragedy. President Biden’s final calculation is something to consider soberly:

“So let me ask those who wanted us to stay: How many more — how many thousands more of America’s daughters and sons are you willing to risk? How long would you have them stay?

“Already we have members of our military whose parents fought in Afghanistan 20 years ago. Would you send their children and their grandchildren as well? Would you send your own son or daughter?

“After 20 years — a trillion dollars spent training and equipping hundreds of thousands of Afghan National Security and Defense Forces, 2,448 Americans killed, 20,722 more wounded, and untold thousands coming home with unseen trauma to their mental health — I will not send another generation of Americans to war in Afghanistan with no reasonable expectation of achieving a different outcome.

“The United States cannot afford to remain tethered to policies creating a response to a world as it was 20 years ago. We need to meet the threats where they are today.”

Dear Vinnie, every time I find myself struggling to absorb certain news, I head to your blog. So here I am again after consuming so much social media content about the US withdrawal from Afghanistan.

I agree with your point of view; at the same time though, my heart breaks for the Afghan people. Historically, Taliban aren’t known to keep their word. So while the withdrawal might be the best option for US national interests, it is more or less a death sentence for the Afghan commoner, especially as we read of Taliban having already gone back on the agreement made. 😦

LikeLike

I agree completely, although I am not sure that the US was doing a good job of protecting civilians in the rural areas. The situation is completely consistent with the classic definition of a tragedy–no good outcomes.

LikeLike